True words are not here / Clouds scatter and fly in the sky / Ah, at the bottom of shining April / Gnashing, burning coming and going / I am an asura

—Kenji Miyazawa, “Haru to Shura” (trans. Tomiyama Hidetoshi and Michael Pronko)

Other people have noted this, but I think it is important to reiterate: this is not *really* a Studio Pixel game, not beyond the programming and engine. Haru to Shura is more essentially understood as Kiyoko Kawanaka’s brainchild. I get this out of the way because going in expecting Kero Blaster or Cave Story is going to induce some kind of shock, as this is, mechanically and structurally, a very standard adventure game. You collect items. Do small scale puzzle solving. There is a small amount of resource management, and navigation is largely confined to a chambered setting that expands only in small ways. These mechanics provide choice and momentum but they are more flavor than primary draw.

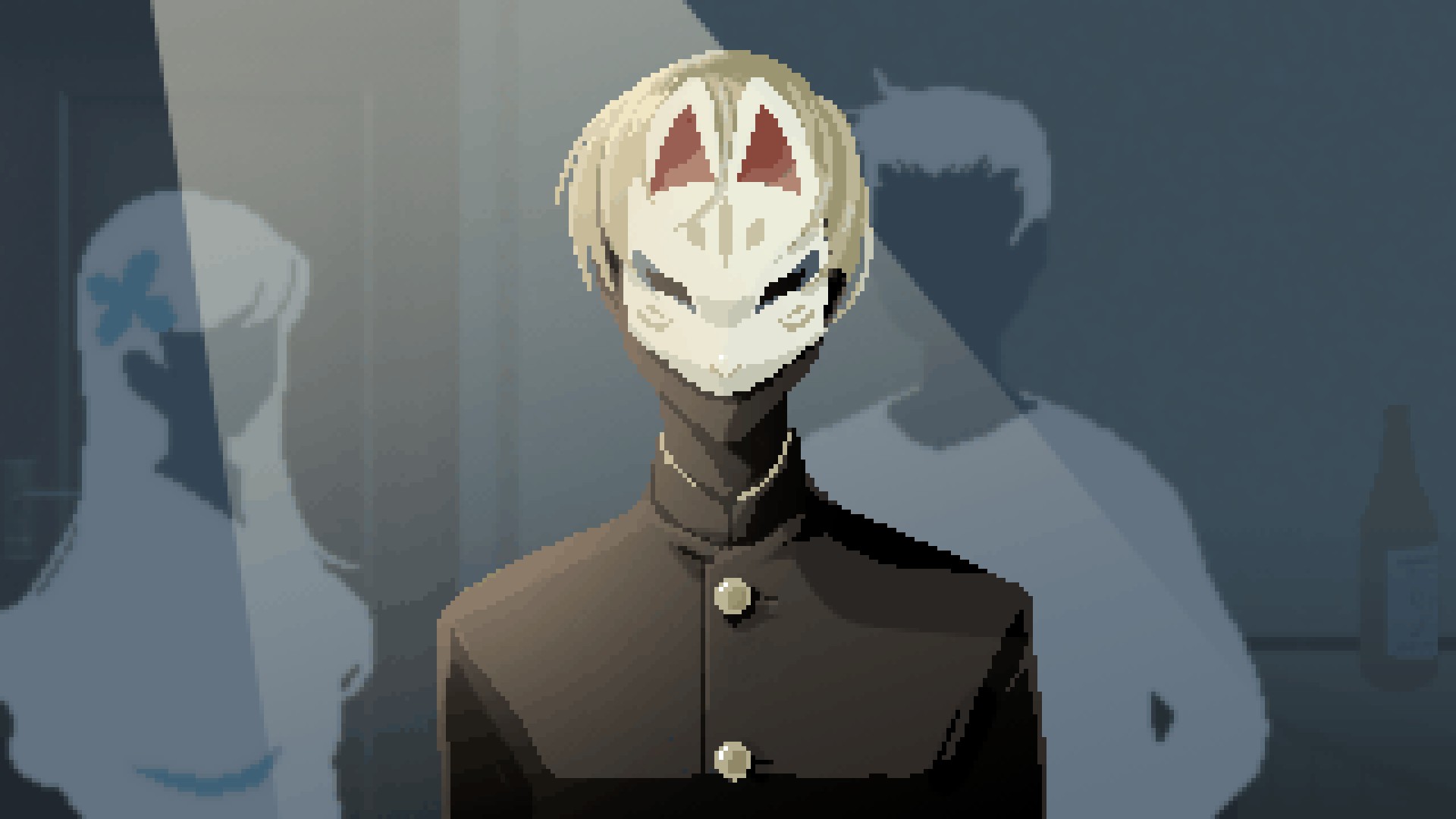

The draw here is going to be narrative. Named for one of the more famous Miyazawa poems, and not the Haru Nemuri debut album (which I listened to after playing! and it’s quite lovely!), the literally translated “Spring and Chaos” follows two young men, the fox-masked Chihiro and the bedsheet ghost garbed Yoru. Chihiro functions as a sort of silent protagonist, though not quite; his thoughts and feelings are plainly elocuted in object descriptions, in dream sequences, in inner monologue, while his outward expressions remain limited to pantomime through which we find interpretation in Yoru. Yoru, meanwhile, works as his structural foil, and their relationship in the ambiguous Eden forms the backbone of the story here.

Eden as figured in Haru to Shura functions as a familiar kind of purgatorial space for much of the game. The denizens, a small group of just under ten people, all like to remind that Eden is a place where bad things can’t happen, where suffering doesn’t exist. This goes so far as concepts like “death” and “pain” and “illness” cannot be conceived of by the cast. Chihiro and Yoru, as strangers to this world, though foggy of memory and self, find themselves as interlocutors, ostracized in part for the knowledge of suffering. Another figure also by the name of Yoru, meanwhile, seems the primary arbitrator of this suffering, an intrusive and capricious figure that disrupts the uneasy and contorted peace of Eden.

This is more or less the first half of the game. You begin the game within the mundane daily rituals of Chihiro, interrupted in smash cuts by an unnamed person’s attempted suicide, and then you are sent to Eden, playing out this little Buddhist mystery. The second half, meanwhile, changes structure slightly. Eventually, you return to the mundanity of Chihiro’s life, and details on both his life and the life of Yoru are filled in. When Chihiro inevitably returns to Eden, his reconnection with Yoru, all knowledge in tow, branches into forking endings. They function along a spectrum of compromised, capital-R romantic failings leading towards a definitive “happy ending.” There’s a sort of mythicness to everything here, the red thread between these infirm and listless souls always “present,” and perhaps too a “fic” quality, the self-reiterating conclusions, the sense of longing and loving that develops through each of those loops. While the broad strokes are never surprising, there is something special here.

Haru to Shura, in its cycles of death and rebirth as two souls adrift find grounding in each other, mirrors this in setting, the moves between late spring, mid winter, early spring, all these different moments of the year punctuated either in death or in life. I joked about this to a friend but Ian Bogost’s Seasons came to mind, similarly coming with an extraordinarily small file size meant to suggests the restrictions it was built within, and to evoke console generations past (Bogost’s is distinctly Atari, here it’s more nebulous but retains the lanky figurines and tightened color palette of that Atari vision). The joke was that Haru to Shura was just that if it meant anything at all. Time is always expanding and compressing here, the chapter notes of nights meaning more and less at a given time because the pacing is always in flux, our temporal placement always shifting. But those great markers of seasons always give us some insight. Eden itself maybe complicates it further, a space coated in a perpetual winter. Every time Chihiro sits down on a bench outside he reminds you how cold it is. Soft pixel snow drapes every surface, every awning shade. But it’s not so great a trick; of course purgatory would suggest staticity. When we exit Eden, here and then, we are reminded of the cycles that exist outside of us.

A few frayed threads exist further in the text that add something in their irresolution. Chihiro, in his “real” life, is a handsome young man, quiet but swooned over by his female peers. He suffers from headaches he seems to not want to fix, whether as a type of punishment, a bashful insecurity in the face of his mortality, a youthful sense of immortality, it’s left ambiguous. We get access to him only piecemeal, but much of it is how he is contextualized by others. He has a reputation, undeserved most likely, as a player, due to his looks. Classmates gossip about how he sees the doctor regularly and how the presumption is he knocked a girl up. We never really get an answer whether any of this is true, but his self-imposed isolation and his budding affection for Yoru suggest these rumors are just that, perhaps even displaced suspicion of his sexual difference.

Yoru, meanwhile, is a man succumbing to something we never get the name of. Eden, his fantasy and escape, exists to mask his fear of what comes next. We don’t get a definitive answer whether what he has is terminal or not; each ending offers slightly different variations on yes or no, but what remains a constant is Eden, its fragility and delusions. Yoru’s relationship with Chihiro offers an out, a reminder of what life could be instead, and his attraction is tinged with jealousy and frustration. He is a little older than Chihiro, we’re not told by how much but he is no longer in school at least, and he envies that youthful naivete, and in the “true ending” he even scolds him directly for his dishonesty with his physician.

Naturally they’re both changed by their encounter, but the game’s final grace note is that “true ending,” again a scene almost out of time, where the two may or may not recognize each other, but find connection again outside of Eden. After a chance encounter at the hospital, Chihiro follows Yoru with puppy-dog affection, hiding behind bushes when he would see him off, monitoring him and tending to him excitedly and bashfully. They exchange numbers. They laugh, a CG-render showing us their first smiles on screen. A promise is made for Chihiro to come visit. Whether this is a flashback to their faithful first meeting or a kind of do-over of it, a kinder timeline established, we don’t quite know. Still, we see our boys smile, and it’s so capital R Romantic. Kawanaka, I feel, trusts that that is enough in the moment, for them, for us.