These reviews are x-posted from a previous blog ♥

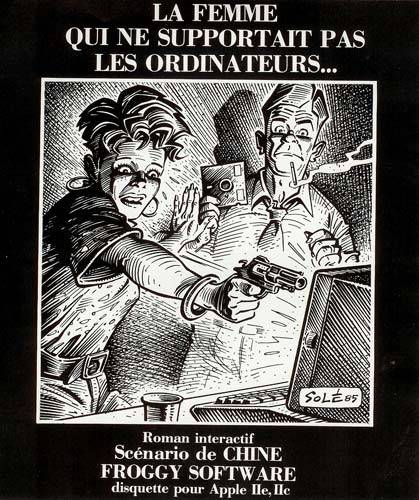

Le femme qui ne supportait pas les ordinateurs

"the very first understanding that i had that it was not a place like any place and that the interaction would be different was when people began to talk to me as though i were a man. when they wrote about me in the third person, they would say “he.” it interested me to have people think i was “he” instead of “she” and so at first i did not say anything. i grinned and let them think i was “he.” this went on for a little while and it was fun but after a while i was uncomfortable. finally i said unto them that i, humdog, was a woman and not a man. this surprised them. at that moment i realized that the dissolution of gender-category was something that was happening everywhere, and perhaps it was only just very obvious on the net. this is the extent of my homage to Gender On The Net."

The more things change the more they stay the same. Obviously a straight-forward feminist parable, not exactly nuanced, but prescient, if you'll forgive the hack choice of words; even before we had the internet as we knew it, women were getting harassed through and by computers. The anonymity of masculinity remains a lonely safeguard in many cases. In reality, the online is a constant; "pandora's vox," an article that still floors me in the truth of how we must be online, was written in 1994. The little excerpt above is not wholly germane, but it shares a sort of collapse of the temporal with Ordinateurs. Gender is more mutable online than anywhere else, and yet it is so very present in all interactions, as are the many other intersecting categories of self, race, class, sexuality, ability. My French is rough, I had to DeepL translate a good portion of this, but this isn't about dazzling you with prose; if you're playing it now, you're playing a time capsule that has been re-created and re-iterated ever since, aphoristic, not nearly enthralling on its own terms, but a piece of history that shows no matter how much our technology changes the core experiences of being here, online, are prone to staticity.

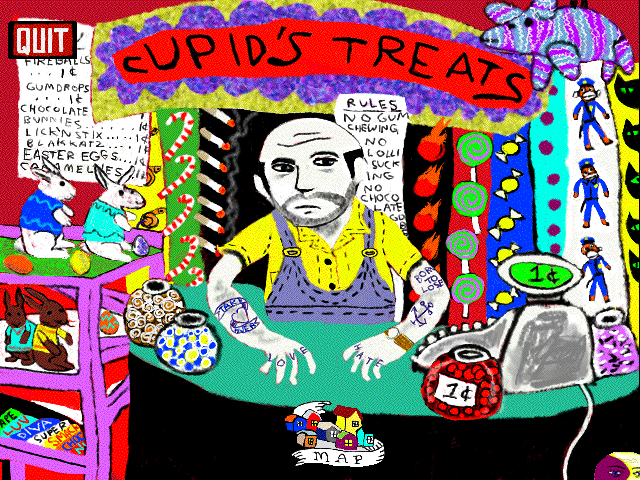

The soft spoken David Sedaris narration and the Fugazi/Dischord Music workings and the tactile vignette structure giving way to beautifully elocuted short stories for young readers are infinitely more artistically accomplished than nearly anything else in the medium. I laughed a lot, the mundanely-observed surrealism is very effective and is exactly what I think a lot of people's nostalgia for old Pajama Sam-styled games or even more infantiely Jumpstart and Purple Moon CD-ROMs are looking for in a less condescending package. Amy Rose Spiegel calls the game empiricist, and I think that's right, the organization of the game is all about observation and discovery with the connective tissue being space and context. We're in Cortland, our base of operations is the eagle-eye view of the map, and all our interactions as June Bugg and Lily are about them finding something and figuring out what's up with it. There is no real linearity here, instead we just have little graceful clips of narration informing us of the lives of the people around our duo. It's the joy of point-and-clicks without the tedium of pixel hunting or need for obtuse, gating puzzles. It's art for kids without ever presuming less of what children are capable of. It is very small form; it's hard to say more novel about this given what and how it is, but it can't be overstated how clear a vision this was, how light and warm the hands that went into it. My only wish is that the way it is currently accessible to us was more functional, and that the way it was discussed culturally didn't have the pallor of Duncan's death over it. I think it's disrespectful of her memory to dwell on that mystery when discussing these games when by all accounts she deeply wanted her trilogy of games to be remember for what they did and for how undeniably beautiful they were.